What Founders Can Learn from the Story of Silicon Valley

In 1848, gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill in California’s Sierra Nevada foothills, and within months, the world was rushing west. Hundreds of thousands of people from every continent flooded into California during the Gold Rush, lured by dreams of quick riches. What they found was as much chaos as opportunity. Mining camps exploded overnight into muddy tent cities brimming with rugged fortune-hunters. Law and infrastructure lagged far behind the gold seekers; early California was a Wild West, a land of immense wealth and lawlessness where survival favored the bold. In this crucible, a distinct entrepreneurial spirit took root. Those who thrived often weren’t the prospectors with pans in riverbeds, but the savvy traders, bankers, and inventors who sprang up to serve and protect the commerce flowing from the gold fields.

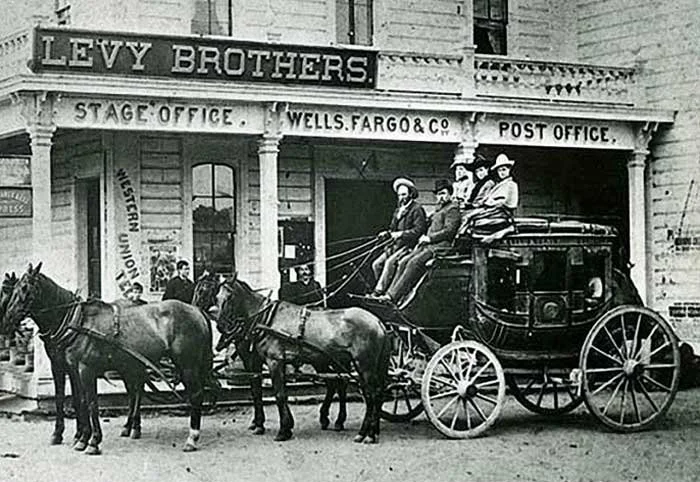

Amid the tumult, a pair of East Coast entrepreneurs saw opportunity in the needs of the miners. In 1852, Henry Wells and William Fargo launched a startup Wells, Fargo & Co. to provide reliable shipping and banking for California’s booming economy. At a time when sudden strikes of gold could make a miner rich but highwaymen and wildcat banks could make him poor again overnight, Wells Fargo offered something revolutionary on the frontier: trust. They contracted stagecoaches to speedily ferry gold dust, important documents, and valuables across wild terrain, and they set up banking offices where miners could convert gold into secure paper drafts or loans. Armed guards and stout safes protected the precious cargo, earning Wells Fargo a reputation for reliability in an era of volatility. One account notes that the company’s “armored stagecoaches and heavily guarded facilities helped build trust among miners and businesses,” making Wells Fargo a cornerstone of California’s young financial system.

Gold miners in El Dorado, California, during the early 1850s Gold Rush. Thousands of fortune-seekers poured into the hills, embodying a new spirit of risk and opportunity.

This entrepreneurship under fire helped civilize the Wild West economy. Wells Fargo not only survived bank runs and stagecoach robberies; it thrived, stabilizing the boom-bust region with much-needed financial infrastructure. By the end of the 1850s, its red stagecoach logo had become a beacon of dependability from San Francisco to the remote mountain diggings. From the feverish chaos of the Gold Rush, California emerged with the foundations of a modern economy, with institutions like Wells Fargo paving the way for modern banking practices. The ethic was set: in California, even in rough-and-tumble times, ingenuity and enterprise could create order, and great fortunes. One young man who arrived in this climate of opportunity, determined to build his own empire, was already taking notes.

Wells Fargo Stagecoach in front of Levy Brothers in Pescadero, California 1890.

Leland Stanford

In 1852, a newcomer stepped off a ship in gold-rush San Francisco with big aspirations. Leland Stanford was a lawyer by training, but like so many drawn west, he reinvented himself on California’s frontier. He started as a merchant supplying miners’ goods, turning a general store into the seed of a business empire. Stanford had an instinct for infrastructure – big, bold ventures that could serve and profit from California’s growth. Within a decade, that instinct would vault him into one of the greatest entrepreneurial feats of the 19th century: building America’s first transcontinental railroad.

Stanford joined forces with three other ambitious businessmen (Collis Huntington, Charles Crocker, and Mark Hopkins, collectively the “Big Four”) to found the Central Pacific Railroad. In the 1860s, backed by federal loans and their own iron will, they undertook the herculean task of laying rail tracks eastward over the towering granite of the Sierra Nevada. Stanford, named Central Pacific’s president, became the public face of this audacious enterprise. He even entered politics as California’s governor during the Civil War, leveraging his influence to support the railroad cause. On May 10, 1869, at Promontory Summit in Utah, Leland Stanford ceremonially drove a golden spike into the final tie, uniting East and West in a continent-spanning network of iron. The iconic photograph of that moment shows two locomotives nose-to-nose, champagne bottles held aloft, and men shaking hands. It was a scene of triumph and transformation: the railroad reflected power and promise, replacing the brute strength of human labor with ingenuity.

Leaders of the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroad lines meet and shake hands, May 10, 1869. (Image credit: Stanford University Archives)

For Stanford, the railroad brought a personal fortune on a staggering scale. By connecting California’s bounty to national markets, he and his partners became railroad barons with wealth and power to match their vision. Yet Stanford’s story took a poignant turn that would leave an even more enduring legacy. In 1884, his only child, 15 y.o. Leland Jr. died of typhoid fever. Grief-stricken but determined to do something meaningful with the fortune railroads had brought them, Stanford and his wife Jane made a stunning decision: “The children of California shall be our children. It is our hope to found a university where all may have a chance to secure an education such as we intended our son to have,” Leland Stanford declared. In that pronouncement, the seed of Stanford University was planted.

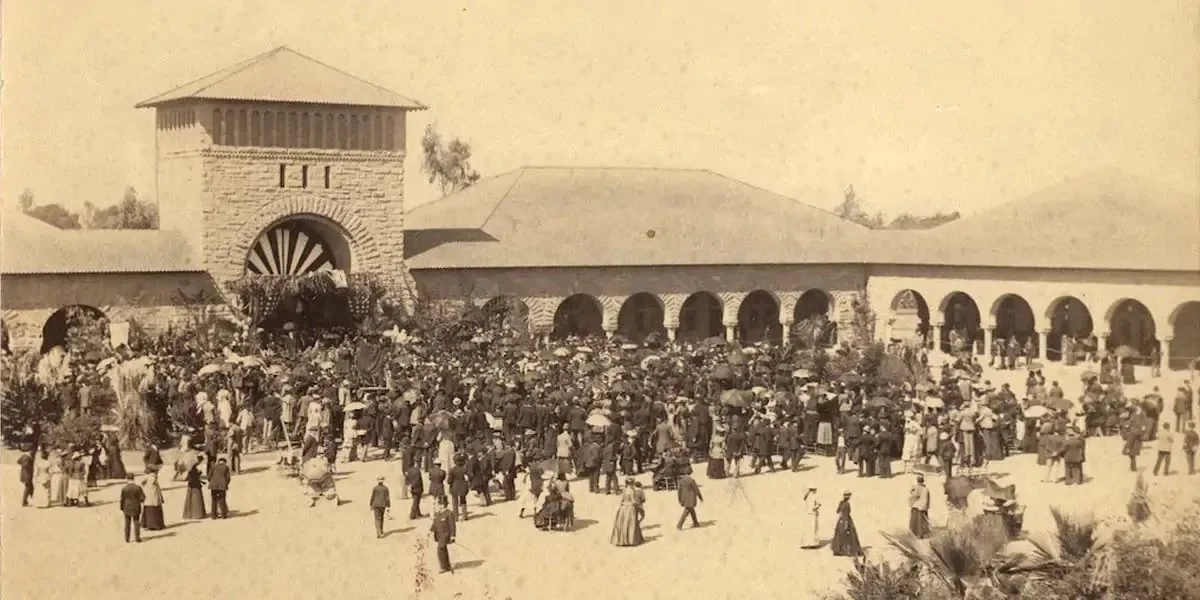

They broke ground on the Farm (their Palo Alto stock farm) and 1891 opened Leland Stanford Junior University. It was an act of faith in the future. Here was a new kind of Western university, born not of church or state, but of entrepreneurial fortune and frontier idealism. Stanford poured his railroad wealth into grand sandstone buildings, gleaming laboratories, and scholarships for promising students regardless of gender or background. The campus’s layout, on the former horse farm, symbolized cultivation – an open quadrangle in the California sun, ready to nurture ideas. Jane and Leland Stanford had effectively transformed personal tragedy into a gift for posterity: a university dedicated to innovation and the work ethic that had fueled California’s rise. Little could they imagine that this act of philanthropy would, over the coming decades, help turn the valley around their farm into fertile ground for world-changing inventions and industries.

Stanford University officially opened its doors on October 1, 1891.

Stanford University

From its earliest days, Stanford University bristled with an ambitious energy befitting its frontier genesis. In an era when most elite universities sat comfortably on the East Coast, Stanford’s founders set out to import excellence to Palo Alto. They attracted top-tier thinkers and talent to what was then still a rural expanse of orchards and oak trees. Early faculty included renowned scholars drawn by the promise of a school unencumbered by Ivy League traditions. By the 1920s and 30s, Stanford had planted the seeds of a world-class science and engineering program. When Nobel Prize-winning physicist Felix Bloch joined the faculty in 1934, or pioneering geneticist Lewis Terman led psychology research, it signaled Stanford’s determination to populate its halls with ambitious minds on par with any in the world. Over the years, this strategy paid off richly: today Stanford is home to dozens of Nobel laureates, breakthroughs and big ideas having become part of its DNA.

An aerial view of Stanford University campus, captured in the early 1920s.

You don’t hear much about the Eastern Establishment these days. But there was once a time when being respected in business, politics, and many other areas meant you practically had to come from the East Coast. The influential figures, wealthy financiers, and Old Boys’ Club members all seemed to be alumni of Harvard, Yale, or another prestigious eastern institution. Back then, California simply wasn’t considered part of the major league.

Frederick Terman, a Stanford engineering professor, and later dean, passionately believed that Stanford should actively support local industry. Terman (often called “the father of Silicon Valley”) took an unusually hands-on approach with students and researchers. Instead of urging graduates to head East for jobs, he encouraged them to stay in California and start companies. Terman didn’t just give pep talks; he rolled up his sleeves and helped make it happen. In one famous example, he mentored two young engineering graduates, Bill Hewlett and Dave Packard, who were tinkering with electronics. Terman convinced them to follow their entrepreneurial instincts and even helped secure funding for them. In 1939, Hewlett and Packard set up a small electronics company in a one-car garage in Palo Alto, with a mere $538 in working capital. That humble shed at 367 Addison Avenue (now a private museum) became legendary as the “HP Garage”, widely celebrated as the birthplace of Silicon Valley. The audio oscillator they built there was their first product (Walt Disney Studios famously bought some for the movie Fantasia), and it launched what would become Hewlett-Packard, one of the Valley’s first tech companies. More importantly, it proved Terman’s philosophy right: world-class companies could be built right at home in Palo Alto.

Moreover, world events would soon amplify Stanford’s role as a crucible of innovation. During World War II, Frederick Terman left campus to lead a top-secret Harvard laboratory developing radar jammers to protect Allied bombers. Returning after the war, Terman brought back technical expertise and a vision for Stanford’s future. He saw that the Cold War government was pouring money into science and defense research, and he was determined that Stanford and California should be at the forefront. “He definitely felt that there was a game change after the Second World War…there was going to be government money to sponsor research. He knew some people in the industry. And he said there were really three elements here: the government money, the university, and the industry”. Terman’s plan was bold: tightly weave those three elements into a virtuous innovation cycle. Stanford would provide top-notch education and research; industry would provide real-world problems and jobs; government grants would fuel advanced labs. He wanted a tight tie between industry and the university, and Silicon Valley was born with that model.

In 1951, Stanford took Terman’s vision a step further by creating the Stanford Industrial Park, the first of its kind in the nation. The university carved out 209 acres of campus land to lease to high-tech companies. Suddenly, fledgling tech firms could set up right next door to Stanford’s labs and classrooms. Early tenants included microwave pioneer Varian Associates (founded by Stanford alumni), a young Hewlett-Packard, and even Eastman Kodak and General Electric looking for a West Coast R&D outpost. Notably, Lockheed Corporation moved its new missile and space division into the area in 1956, lured in part by Terman’s promise that Stanford would help train its engineers. This university-industry partnership was groundbreaking. By clustering industry around Stanford, Terman turned the mid-Peninsula into a hotbed of innovation. The orchards began to give way to laboratories and machine shops, as “the Farm” evolved into a seedbed for electronics companies.

These early developments laid the cultural foundation for the Bay Area. A community was forming where academics and entrepreneurs freely mingled, where starting a company was celebrated rather than shunned. Risk-taking was in the air. The valley’s first-generation tech entrepreneurs, like Hewlett and Packard, became local role models, showing that you didn’t have to be in New York or Boston to invent the future. Still, in the early 1950s, Santa Clara Valley’s tech scene was small and primarily focused on military electronics (radar equipment, microwave tubes) and instrumentation. The spark that would ignite Silicon Valley’s explosive growth was yet to come.

Stanford Industrial Park, 1953

The Making of Silicon Valley

If Gold Rush prospectors once mined the hills of California for flecks of gold, a new generation in the mid-20th century would soon be mining something even more precious in the Valley: ideas. By the late 1940s, the Santa Clara Valley still sported pear orchards and sleepy suburbs – but it was also sprouting electronics labs and defense contractors, thanks partly to Stanford’s efforts. The stage was set for the next great rush, this time for silicon and technological treasure.

A pivotal moment came in 1956 when a brilliant scientist and Nobel Prize winner, William Shockley, moved west. Shockley had co-invented the transistor at Bell Labs, a breakthrough that would revolutionize electronics, and he decided to establish his semiconductor laboratory in Mountain View, near Palo Alto. This move ‘brought silicon to the Valley,’ literally and figuratively. Shockley Semiconductor, as his venture was called, hired a team of bright young PhD engineers who relocated eagerly to California, sensing they could build something groundbreaking. They were right, but not in the way they expected. Shockley’s managerial style proved dictatorial and stifling. In the summer of 1957, eight of his best researchers revolted, quitting en masse to form their own company. Shockley was furious. He viewed their departure as a personal betrayal and angrily dubbed them the “Traitorous Eight.” This nickname became legendary and marked a turning point in business culture. As one account put it, “It was this act of defection that created the magic culture of the Valley, shattering traditional assumptions about hierarchy and loyalty.” In leaving an established Nobel laureate’s lab to start fresh, these young engineers embodied the maverick entrepreneurial spirit that Silicon Valley now prides itself on.

The new company the Eight founded was Fairchild Semiconductor. It was no garage startup scrounging for pennies; in fact, it became the Valley’s first big venture-backed startup, funded by an early New York investor, Arthur Rock. This new form of finance venture capital stepped in to back technologists with risky ideas in hopes of a resounding payoff. Fairchild Semiconductor repaid the faith brilliantly. Over the next decade, it produced revolutionary silicon transistors and integrated circuits that would power the space race and the computer industry. More importantly, Fairchild became the cradle of dozens of other startups: when some restless engineers felt Fairchild was growing too bureaucratic, they, too, spun off to start new companies. Intel, founded in 1968 by Fairchild alumni Robert Noyce and Gordon Moore, was just one of the many ‘Fairchildren.’

Fairchild Semiconductor founders in the company’s Mountain View lobby (Gordon Moore, Sheldon Roberts, Eugene Kleiner, Robert Noyce, Victor Grinich, Julius Blank, Jean Hoerni and Jay Last)

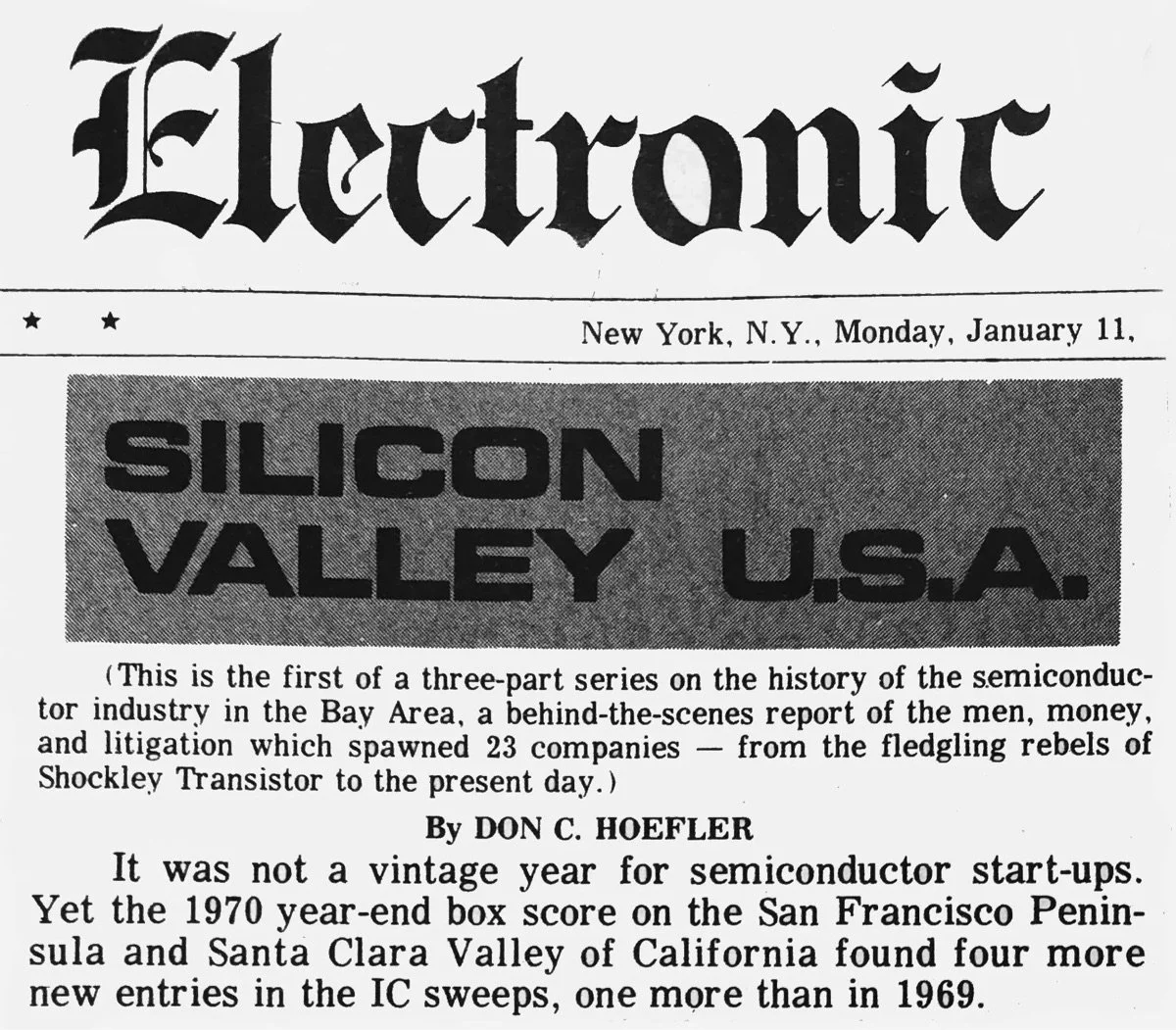

Around this time, the moniker Silicon Valley was coined. In 1971, a local trade newspaper used the term to describe the growing cluster of silicon-based semiconductor companies. The name stuck, and for good reason. By 1970, Santa Clara Valley’s orchards had largely given way to industrial parks, office campuses, and suburban tract housing for thousands of new tech workers. The valley that had once shipped plums now shipped silicon. However, what made Silicon Valley truly unique wasn’t just the concentration of companies – it was the culture and network of people connecting them.

Frederick Terman’s vision from a decade earlier had come true beyond his wildest dreams. As one observer noted, the funding of the Traitorous Eight’s startup in 1957 “was arguably the first big venture deal in the Valley; from that moment, teams with grand ideas and stiff ambition could spin themselves out…Talent had been liberated. A revolution was afoot.”

First use of the name in print. Electronic News, January 11, 1971

Risk-Taking Culture

From the Shockley saga and the Fairchild experience, Silicon Valley developed a culture unlike any other industrial region. A spirit of risk-taking and openness to new ideas was at its heart. These young engineers had shown that it was not only acceptable but even laudable to quit a secure job and start a risky company in pursuit of an idea. In more traditional business centers, leaving an established firm might label you disloyal; in Silicon Valley, after the Traitorous Eight, it became part of the lore – a bold move that could change the world. This cultural shift cannot be overstated. Employees saw that establishing a startup was a viable and exciting path. Failure was not terminal. One could fail and try again, and lessons learned were valued more than stigma.

Hand-in-hand with this risk-embracing culture came the rise of venture capital to fund innovation. In the late 1950s and 60s, traditional East Coast banks were often unwilling to bet on unproven technology startups. So, a new kind of financier emerged to fill the gap, and many of them were inspired directly by the Fairchild story. Arthur Rock, the banker facilitating Fairchild’s founding, became one of the first true venture capitalists. He later moved to Palo Alto and continued to back startups, including Intel in 1968 and Apple a decade later. Following in his footsteps, one of the Traitorous Eight, Eugene Kleiner, partnered with Tom Perkins (an ex-HP executive) to start Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers in 1972 – a venture firm that would fund dozens of future Silicon Valley successes. Out of nearby San Francisco, Don Valentine, who had worked in marketing at Fairchild, founded Sequoia Capital in 1972, another legendary VC firm. By the 1970s, Sand Hill Road next to Stanford had become lined with venture capital partnerships ready to finance bold startups.

In this fertile environment, the philosophy held that “anyone with a good enough idea can get the capital, the workforce, and the market to make it a reality.” The Fairchild veterans embodied this credo and passed it on by investing in and mentoring the next generation. Money, expertise (workforce), and customers were all increasingly available in Silicon Valley for those willing to try. This was a profound shift. It meant a bright Stanford graduate or a hacker tinkering in a garage had a shot at launching the next big company without moving to New York or pleading with established corporate gatekeepers. Venture capital fueled the Valley’s fire – funding new companies that, if successful, created wealth and experience that then cycled back into funding more companies.

Don Valentine, founder of Sequoia Capital, 1972

Ecosystem

By the late 1970s, the virtuous cycle was in full swing. Silicon Valley had become a self-sustaining ecosystem – a kind of perpetual innovation machine. Crucially, all the necessary ingredients for technological entrepreneurship were now locally present and reinforcing each other: world-class universities supplying talent and research; pioneering companies training skilled workers and spawning new ideas; experienced mentors and managers who had grown up in those companies; abundant venture capital willing to take risks; and a cultural norm that encouraged collaboration, experimentation, and even friendly competition.

In 1976, when Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak founded Apple Computer in a Cupertino garage, the environment was ready to nurture it – Mike Markkula, a former Fairchild and Intel employee-turned-angel investor, provided Apple with early funding and business guidance, perfectly exemplifying how one generation enabled the next. By the 1980s, a new wave of Silicon Valley companies emerged (Sun Microsystems, Cisco, Adobe, and many more), followed in the 1990s by the Internet boom (pioneered by companies like Netscape, Yahoo, Google) – each wave drawing on the Valley’s ecosystem and then amplifying it further.

This accumulated interplay of elements made Silicon Valley unique and hard to copy. Other regions had great universities or large tech firms, but no other place integrated academia, industry, capital, and culture so effectively. The Valley also benefited from timing – it grew alongside the Cold War defense spending and the space program, which provided contracts and urgency for electronic innovation in the 50s and 60s. Then, it pivoted seamlessly to serving the civilian computer and software markets that exploded in the 70s and beyond. Through it all, the people in Silicon Valley kept alive a certain frontier optimism – a sense that the next big thing could be invented by a few folks in a garage or lab and that it was worth taking a chance on.

Epilogue

A sun-kissed valley of orchards became the incubator for an unprecedented experiment in innovation. California's open land and open-minded culture provided the canvas; Stanford University provided the spark and support; dreamers and doers provided the human drive.

Today, every ambitious city dreams of becoming “the next Silicon Valley.” From Berlin to Bangalore, governments fund tech parks, universities launch incubators, and investors talk of ecosystems. And yet, something often feels missing.

Because Silicon Valley was never just a cluster of tech companies. It wasn’t built in a decade, and it didn’t happen because someone drew a boundary on a map and said, “Innovation happens here.”

It was a generational phenomenon. Each layer: Wild West, industrialists, scientists, founders, added something to the DNA. It wasn’t designed. It evolved. That’s what made it powerful.

And that’s what many forget: you can’t copy the Valley by copying its output. You have to nurture the values that created it in the first place – risk-taking, resilience, intellectual freedom, and the radical belief that the future can be invented.

Silicon Valley is more than a place. It’s a legacy of motion. From panning for gold to mining code, from guarding gold deliveries to backing bold ideas, the soul of this land has always echoed with entrepreneurial spirit.